Airplanes, Oil, Elections, and Zeno's Paradox in Iran

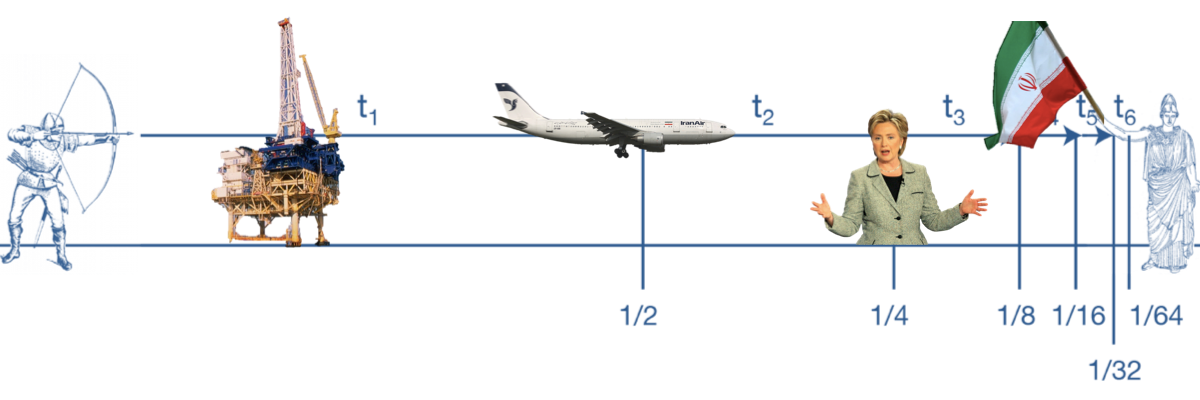

Zeno of Elea was an Ancient Greek philosopher most famous for his four paradoxes on the relationship between space and time. The most famous “Zeno’s Paradox” is the “Dichotomy Paradox.” Imagine you wish to travel from A to B. In order to reach your destination, you will need to walk half the distance. You will then need to walk half of the remaining distance (a quarter of the total distance), and then half of the remaining distance (an eighth of the total distance), and so forth. Continuing in this manner, as the basic math shows (½ + ¼ + ⅛ …), it would take an infinite number of steps to reach point B.

On Iran’s journey from A to B, from sanctions relief to economic resurgence, the Iranian and European business communities have been waiting for three key milestones: Iran’s acquisition of its first new airliners, the entry of the first international oil company to Iran, and the conclusion of the seemingly everlasting US election. There have been developments in each area this week.

First, Tim Hepher and Parisa Hafezi at Reuters report that Airbus has made progress in the effort to secure financing for its deal to sell 118 planes to Iran Air. However, the lease finance, which may come via Dubai, would only cover the first 17 planes.

Second, Benoit Fauçon at Wall Street Journal was the first to report that France’s Total and China’s CNPC would be the first international oil companies to make a post-sanctions investment in Iran’s gas industry, working with Iran’s Petropars to develop the South Pars gas field in a USD $6 billion deal. However, the signing ceremony was only for a Heads of Agreement, and the “deal is a draft that still must be completed over the next six months” according to Iranian officials.

Finally, we have passed election day in the United States, and after months of uncertainty, Iranian officials and the business community now know that Donald Trump will lead the United States for the next four years. While the outcome is concerning due to his outspoken criticism of Iran, at the very least companies can begin to evaluate political risk more concretely as they weigh investments in Iran and elsewhere. However, the nature of the US election and the discourse between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump meant that there was no substantive discussion of Iran policy by either candidate. While the Iran-focused personnel at the State Department and the U.S. Treasury are unlikely to change, it will likely take several months for the new Trump administration to signal its overall approach on implementation of the nuclear deal and related issues.

It seems, therefore, that in each instance where there is progress in Iran’s post-sanctions agenda, something like Zeno’s Paradox remains in effect. For every milestone reached, another remains frustratingly far away, and the ultimate goal of profits and economic growth seem tantalizingly out of reach.

Part of the problem is one of perception, and here, Zeno is once again instructive. His “Arrow Paradox” describes the relationship between motion and time. If you observe an arrow in motion at a single point in time, it will appear motionless. Continuing in this manner, if the arrow is observed at every instant on its journey, it will appear motionless at every instant. Motion, therefore, would seem impossible.

In some ways, the arrow paradox describes the problem of perception and expectation around Iran’s economy. The tendency is to observe the market at a given instant, and to see banking challenges, reputation risk, and political uncertainty as barriers that have prevented trade and investment almost constantly. It might seem that no progress is being made.

The trick to understanding Zeno’s paradoxes is the same as the trick to seeing the progress in Iran’s economic recovery. Worrying too much about how to take the next step on the journey from A to B and about the challenges that presently make that next step difficult, make us blind to the importance of changes in momentum.

As the news from Airbus, Total, and the US Election demonstrates, Iran’s economic recovery is gaining momentum. Key milestones are being reached more quickly, even if the incremental steps are smaller. While the JCPOA nuclear deal took us halfway from the journey from economic isolation to economy resurgence, subsequent steps, represented by the actions and achievements of particular ministries, companies, or individuals, will be smaller. But these steps are now occurring more rapidly. As Brian Palmer explains in Slate, the trick to solving the paradox is to make “the gaps smaller at a sufficiently fast rate.”

This is exactly what is happening in Iran to solve the country's economic paradoxes. A resurgence once considered impossible is slowly coming to fruition.