Sanctions, CBDCs, and the Role of ‘Decentral Banks’ in Bretton Woods III

In a recent conversation on the Odd Lots podcast, Zoltan Pozsar offered an interesting use case for central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), a potentially transformative technology that 86 percent of central banks are “actively researching” according to a BIS survey from 2021.

Pozsar, a former Credit Suisse strategist who is setting up his own research outfit, believes that a new global monetary order is emerging—he calls it “Bretton Woods III.” As part of this order, the adoption of CBDCs will enable central banks to play a more pivotal role in global trade through the formation of a “state-to-state” network that is intended to be independent of Western financial centres and the dollar. In this network, central banks will play a “dealer” role when it comes to providing liquidity for trade among developing economies. Commenting on China’s push to internationalise the renminbi, Pozsar set out his vision:

You need to imagine a world where five, ten years from now we are going to have a renminbi that’s far more internationally used than today, but the settlement of international renminbi transactions are going to happen on the balance sheets of central banks. So instead of having a network of correspondent banks, we should be thinking about a network of correspondent central banks and a world where you have a number of different countries and in which each of those different countries have their banking systems using the local currency but when country A wants to trade with country B… The [foreign exchange] needs of those two local banking systems are going to be met by dealings between two central banks.

In short, Pozsar believes that the adoption of CBDCs will enable the creation of a “new correspondent banking system” built around central banks. But even if central banks do begin to use CBDCs to settle trade, reducing dependence on dollar liquidity and legacy correspondent banking channels, the underlying problem motivating CBDC adoption will remain.

Moving away from the dollar-based financial system is foremost about geopolitics. Globalisation, as we have known it, reinforced a unipolar order. The United States was able to leverage its unique position in the global economy into unrivalled superpower status. In the last two decades, the weaponisation of the dollar further augmented U.S. power—Americans are uniquely able to wage war without expending military resources, which is another kind of exorbitant privilege. As Pozsar notes, the countries moving fastest towards CBDCs are those that are either currently under a major U.S. sanctions program (Russia, Iran, Venezuela etc.) or at risk of being targeted (China, Pakistan, South Africa etc.) These countries recognise “that it is pointless to internationalise your currency through a Western financial system… and through the balance sheets of Western financial institutions when you basically do not control that network of institutions that your currency is running through.” As Edoardo Saravalle has argued, the power of U.S. sanctions is actually underpinned by the central role of the Federal Reserve in the global economy.

Adopting CBDCs would enable countries to reduce the proportion of their foreign exchange reserves held in dollars while also reducing reliance on U.S. banks and co-opted institutions such as SWIFT to settle cross-border payments. However, even if countries reduce their exposure to the dollar-based financial system in this way, U.S. authorities will still be able to use secondary sanctions to block central banks from the U.S. financial system for any transaction with a sanctioned sector, entity, or individual. Any financial institution still transacting with a designated central bank could likewise find itself designated.

Moreover, even if Bretton Woods III emerges, leading to the formation of a robust parallel financial system that is not based on the dollar, central banks will continue to engage with the legacy dollar-based financial system. It is difficult to image a central bank correspondent banking network in which nodes are not shared between the dollar-based and non-dollar based financial networks. As such, the threat of secondary sanctions or being placed on the FATF blacklist—moves that would cut a central banks access to key dollar-based facilities—will remain a significant threat.

Even Iran, which is under the strictest financial sanctions in the world, including multiple designations of its central bank, continues to depend on dollar liquidity provided through a special financial channel in Iraq. A significant portion of Iran’s imports of agricultural commodities continue to be purchased in dollars. Iran earns Iraqi dinars for exports of natural gas and electricity to its neighbour. The Iraqi dinars accrue at an account held at the Trade Bank of Iraq. The dinar is not useful for international trade, and so Iran converts its dinar-denominated reserves into dollars to purchase agricultural commodities—a waiver issued by the U.S. Department of State permits these transactions. The dollar liquidity is provided by J.P. Morgan, which plays a key role in the Trade Bank of Iraq’s global operations, having led the creation of the bank after the 2003 invasion.

The fact that the most sanctioned economy in the world depends on dollar liquidity for its most essential trade suggests that central banks will remain subject to U.S. economic coercion, owing to continued use of the dollar for at least some trade. But even in cases where Iran conducts trade without settling through the dollar, U.S. secondary sanctions loom large.

For over a decade, China has continued to purchase large volumes of Iranian oil in violation of U.S. sanctions, paying for the imports in renminbi. Iran is happy to accrue renminbi reserves because of its demand for Chinese manufactures. But owing to sanctions on Iran’s financial sector, Iranian banks have struggled to maintain correspondent banking relationships with Chinese counterparts. When the bottlenecks first emerged more than a decade ago, China tapped a little-known institution called Bank of Kunlun to be the policy bank for China-Iran trade.

The bank was eventually designated by the US Treasury Department in 2012. Since then, Bank of Kunlun has had no financial dealings with the United States, but that has not eased the bank’s transactions with Iran. Bank of Kunlun is owned by Chinese energy giant CNPC, an organisation with significant reliance on U.S. capital markets. When the Trump administration reimposed secondary sanctions on Iran in 2018, Bank of Kunlun informed its Iranian correspondents that it would only process payment orders or letters of trade in “humanitarian and non-sanctioned goods and services,” a move that was intended to forestall further pressure on CNPC. Ultimately, Bank of Kunlun had far less exposure to the U.S. financial system that China’s own central bank ever will, a fact that points to the limits of a central bank correspondent banking network. For CBDCs to serve as a defence against the weaponised dollar, they would need to be deployed by institutions that maintain no nexus with the dollar-based financial system. It is necessary to think beyond central banks.

What Pozsar has failed to consider is that in a world with two parallel financial systems, a country would not necessarily have a single reserve bank. Alongside central banks, we can envision the rise of what I call decentral banks. If a central bank is a monetary authority that is dependent on the dollar-backed financial system and settles foreign exchange transactions through the dollar, a decentral bank is a parallel authority that steers clear of the dollar-backed financial system and settles foreign exchange transactions through CBDCs. The extent to which Bretton Woods III really represents the emergence of a new bifurcated global monetary order depends not only on the adoption of CBDCs, but also the degree to which the innovations inherent in CBDCs enable countries to operate two or more reserve banks whose assets and liabilities are included in a consolidated sovereign balance sheet.

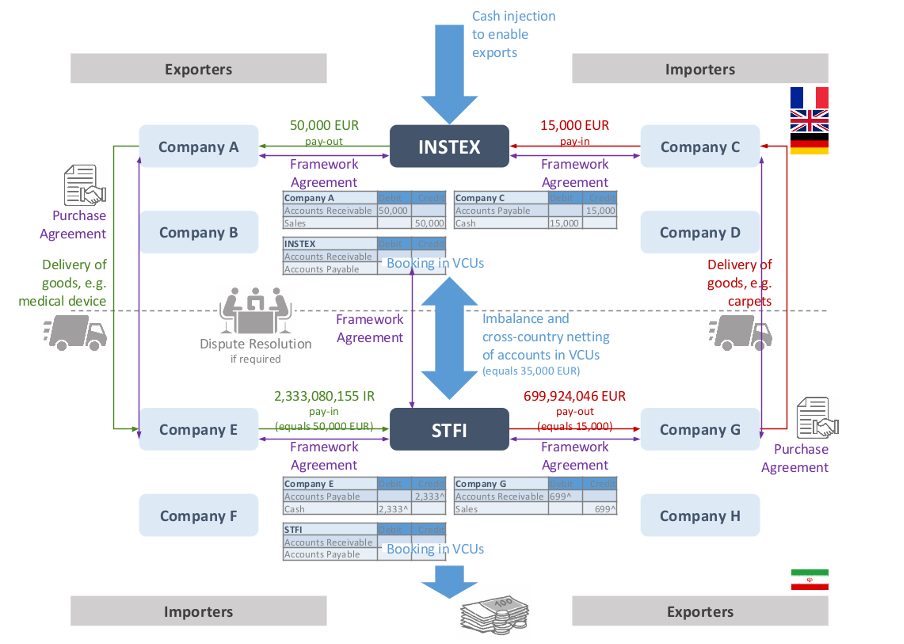

Again, Iran offers an interesting case study for what this innovation might look like. The reimposition of U.S. secondary sanctions on Iran in 2018 crippled bilateral trade between Europe and Iran. Conducting cross-border financial transactions was incredibly difficult owing to limited foreign exchange liquidity and the dependence on just a handful of correspondent banking relationships. France, Germany, and the United Kingdom took the step to establish INSTEX. As a state-owned company, INSTEX would work with its Iranian counterpart, STFI, to establish a new clearing mechanism for humanitarian and sanctions-exempt trade between Europe and Iran. The image below is taken from a 2019 presentation used by the management of INSTEX to explain how trade could be facilitated without cross-border financial transactions.

The model is strikingly like Pozsar’s suggestion that CBDCs will enable central banks to settle trades using their balance sheets, rather than relying on the liquidity of banks and correspondent banking relationships. INSTEX and STFI were supposed to net payments made by Iranian importers to European exporters with payments made by European importers to Iranian exporters, using a “virtual currency unit” to book the trade. The likely imbalances would be covered by a cash injection into INSTEX (Europe was exporting far more than it was importing after ending purchases of Iranian oil). It was an elegant solution, which sought to scale-up the methods being used by treasury managers at multinational companies operating in Iran to purchase inputs and repatriate profits.

Earlier this year, INSTEX was dissolved. Its shareholders, which eventually counted ten European states, lacked the political fortitude to see the project through. Notwithstanding bold claims about preserving European economic sovereignty in the face of unilateral American sanctions, there was always a sense among European officials that Iran was undeserving of a special purpose vehicle. But as the world moves to a new financial order, more institutions like INSTEX will emerge. Pozsar’s vision is bold insofar as he believes central banks will establish new cross-border clearing mechanisms based on CBDCs. But if new digital currencies can emerge to displace the dollar in the global monetary order, so too can new institutions be established.

Pozsar’s vision for Bretton Woods III becomes more convincing if one considers that the emergence of institutions such as decentral banks could lead to the creation of correspondent banking networks that are truly divorced from the dollar-based financial order. However, there remain plenty of reasons to doubt that such a system will emerge. Pozsar appears to have given little consideration to the issue of state capacity. Most countries have poorly managed central banks as it is—in the Odd Lots interview he pointed to Iran and Zimbabwe as early movers on CBDCs. We should have low expectations for the ability of most governments to develop and implement new technologies such as CBDCs or to establish wholly new institutions such as decentral banks. Moreover, the ability of the U.S. to use carrots and sticks to interfere with those efforts should not be underestimated.

There may be compelling structural drivers for something like Bretton Woods III, namely the rise of China and the overall shift in the global distribution of output. But somewhere along the way those structural drivers need to be converted into institutional processes. Bretton Woods is shorthand for the idea that monetary rules are as important for the operation of the global economy as the macroeconomic fundamentals. Countries reluctant to break the rules will struggle to rewrite them.

Photo: Canva